Andrea McCabe

ContributorBuilding Castles With Mathematics

Our family loves to head to the beach. As I sit writing, I hear the waves, marvel over the blues, greens, and browns, and smell sunscreen. Over the years we have built many sandcastles and even participated in a couple of sandcastle building competitions. Now, don’t get the idea that I am some sort of expert sand sculptor. I think of myself as more of a cookie-cutter builder; I tend to build castles with one of those pails that is shaped like a crenelated tower.

Last year, I found myself among a group of math teachers at a conference. Some were the sand-sculpting kind of math teachers; the builders of intricate mathematical dragons and algorithmic statues of Poseidon. We spent the day together solving all sorts of interesting math problems. As some laboured with the numerical equivalent of crenelated pails and simple shovels, others swept sand into spectacular sculptures. Each of us, at times, removing portions of our creation to correct mistakes, making space for new ideas, or imitating the person beside us. Does this sound like math to you?

How do you approach the problem

So often our mathematics education follows a pattern: here is a set of problems, and here are the steps to be used to solve them. I’m not surprised to find students who memorize how to do each problem type, and never think about how the problems are related or if there are other (equally valid) ways to solve the problem. How stressful to be faced with a set of problems that we don’t remember the solution to! This is the stuff of examination nightmares! What if we were to understand math education as filling our tool belt (skills like math facts, exponent rules, and trigonometric identities, etc.), so we can attack problems of a type we have never faced? What if we were to approach an unrecognized problem with confidence, knowing that we are well equipped to explore it, and with the patience to try multiple approaches? This can transform a trauma to be endured into a mystery to be solved

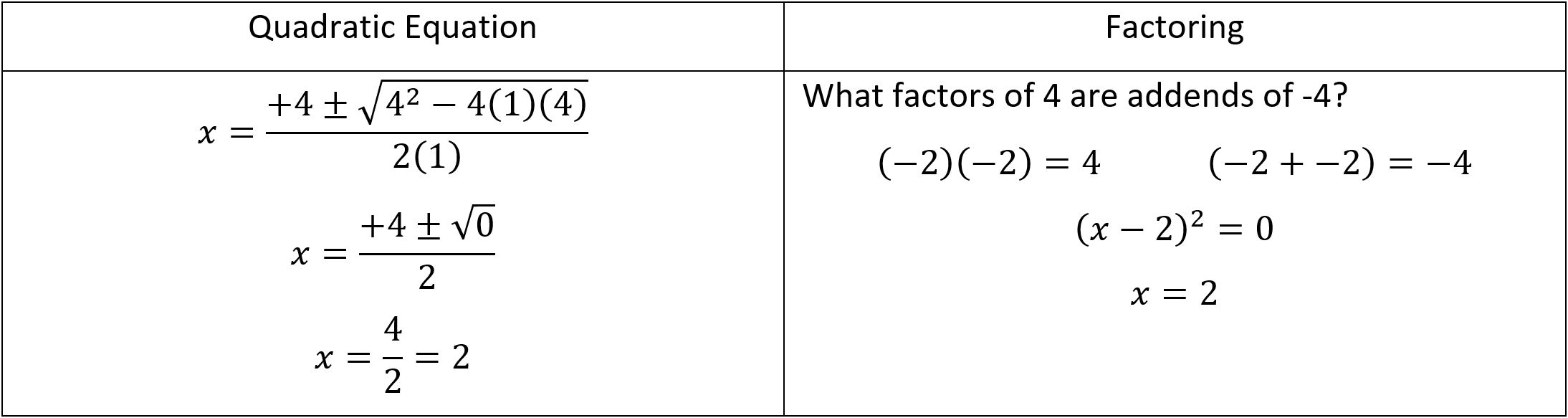

Remember the quadratic equation?

We all know that having the right tool for a job is ideal. Have you ever completed a task the hard way, only to discover that someone else did the same task in half the time and with half the effort? Everyone got the job done, but the quicker solution is preferred. You can see here that factoring might be a quicker, more elegant solution for this equation.

Once we have mastered individual tools, we could approach problems by first thinking about which tool would give the best solution. Think of a Rubik’s cube. The best solvers complete them in seconds using highly efficient solutions, whereas the rest of us can laboriously plod to the same end position after a great deal of effort. Equipped with multiple, practiced strategies, we can tackle problems that require multiples steps, and more than one tool, and not just solve them, but perhaps find more elegant solutions to them. It is no mental leap from here to say that as our craftmanship improves our solutions can be beautiful, not just utilitarian. I think an example from geometry will make my point.

Archimedes famously helped defend Syracuse with his war machines, but unfortunately died at the hand of a Roman soldier despite orders that he not be harmed. Archimedes, a true craftsman, has a long list of accolades, but let’s look at the one put on his tomb:

What is the relationship between the surface area a sphere and the surface area of an open circumscribed cylinder? Archimedes wrote a book on the relationships between these two geometrical shapes, On the Sphere and the Cylinder. You’ll need some information:

How can we approach this problem? Putting some numbers in for the radius and height? Trying some substitution? What is the relationship between the

Archimedes saw that the height of the circumscribed cylinder was exactly equal to twice the radius of the sphere, which means:

Surface area of a sphere = surface area of an open circumscribed cylinder.

There is a beautiful simplicity to this proof, and in any solution that clearly describes how one thing is related to another. There is also a relationship between the total surface area of a closed circumscribed cylinder and the sphere, and their respective volumes. Why don’t you find them? Finding patterns is so satisfying!

However, finding patterns and elegant solutions can involve a lot of repetition and hard work, which brings me back to the necessity of good tools. Sand sculptors expertly use tools like pails, shovels, and trowels to produce beautiful sculptures. There is a lot of practice, time, and effort involved. We, too, need to practice with estimation, number patterns, geometry theorems, and even integrals. Completing math problems – and correcting them! – may seem pointless, but the result is a deeper understanding of how the world works and a new appreciation for the beauty of mathematics and the world around us. God has given us a complex but comprehensible universe, filled with surprising parallels and unexpected relationships. We have been given brains capable of wonder and a drive to know. Mathematics is a set of tools, some mundane and some nearly miraculous, for describing and exploring creation, leaving us with a deeper understanding of the world we are called to steward.

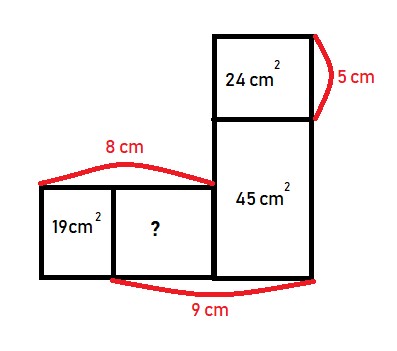

I’ll leave you with one more problem. Pick up your tools to find a beautiful solution to this problem. Happy sculpting!

For Further Exploration:

- Centre for Education in Mathematics and Computing math contests (www.cemc.uwaterloo.ca)

- Books and YouTube videos by Alex Bellos

- Anno’s Hat Tricks by Akihiro Nozaki